AIS in the Lake

Aquatic invasive species (AIS) include plants, animals, and pathogens that may be intentionally or unintentionally introduced into the Basin. Nonnative species—species that were not present at the time of European settlement—were first documented in Lake Champlain as early as 1840. As of 2018, 51 known aquatic non-native and invasive species have been identified.

The Lake Champlain Basin Program was a key partner in the development of the 2005 Lake Champlain Basin Aquatic Nuisance Species Management Plan, along with the states of Vermont and New York and many other groups. The plan sets priorities for AIS control and management and is eligible for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service funding to support programs such as water chestnut control and boat launch stewardship.

Of the known 51 invasive species in the Lake, several are high priority for management:

- Alewife

- Eurasian Watermilfoil

- Golden Clam

- Japanese Knotweed

- Purple Loosestrife

- Water Chestnut

- Zebra Mussel

Other species, while not identified in the plan, are of particular concern to managers:

Learn how volunteers are help remove aquatic invasive species from Lake Champlain in this video from our Diving In series:

More on Aquatic Invasive Species

- Lake Champlain Basin Aquatic Invasive Species Guide

- NY Invasive Species Speaker Series (YouTube Channel)

- Aquatic Invaders Brochure (Spread Prevention Tips)

- Baitfish of Vermont Including Lake Champlain (VTFWD)

- New York Invasive Species Clearinghouse (Cornell University Cooperative Extension and NY Sea Grant)

Alewife

The alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus) is a marine fish species from the herring family that is native to the Atlantic Ocean. Each spring, adult alewives migrate into freshwater rivers to spawn. The young hatch in the rivers, reside there for the summer, and then migrate out to sea in early fall where they mature as adults. Alewives can, however, live and reproduce in freshwater. Alewife populations have become established in the Great Lakes and many landlocked lakes in New York, and the New England states.

In 2003, alewives were confirmed in Lake Champlain when several juvenile fish were found during a yearly forage fish survey by the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department. The number caught in subsequent surveys has increased. A widespread alewife die-off in 2008 (and smaller die offs since) confirmed that large numbers are now present. Although alewives do undergo periodic mass mortality events, the specific cause of the Lake Champlain die-offs is unclear. Long-term monitoring conducted by the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife since the 1990s has shown that alewife have become the dominant forage base in the Lake, replacing rainbow smelt. Research has shown that alewife growth rates in Lake Champlain are higher than those observed in the Great Lakes populations, suggesting that alewife populations are still expanding in Lake Champlain.

Alewives threaten the native species of Lake Champlain and other Basin waters by altering zooplankton communities, competing with other fish for food, and feeding on native fish eggs and larvae. They also pose a threat to lake trout and Atlantic salmon who can experience reproductive failure when feeding on an alewife diet due to a severe thiamine (vitamin B) deficiency. Alewives in Lake St. Catherine have led to decreased water clarity and a threatened smelt population. In February 2006, the LCBP and Lake Champlain Sea Grant co-hosted a Lake Champlain Alewife Impacts workshop to assess the potential impacts of the fish.

More on Alewife

- Alewife Factsheet (VT DEC)

Didymo (Rock Snot)

Didymo (Didymosphenia geminata), or “rock snot,” is a freshwater alga native to cool temperate regions of northern Europe and northern North America. Didymo cells attach to stream beds with a fibrous stalk, forming dense mats with a texture similar to wet wool (as opposed to the slimier feel of other algae species). Research has not shown significant impacts to salmon and trout, but a few studies have shown that didymo can alter local macroinvertebrate species diversity at a bloom site.

Didymo was confirmed in the Lake Champlain Basin in the Mad River in July 2008 and the Gihon River in June 2010 by the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources. In June 2007, didymo was found in the upper reaches of the Connecticut River and soon after in the White River. In August 2007, a small infestation was reported in the lower Battenkill River.

Because its microscopic cells can cling to boats, waders, fishing gear, sandals, and anything else that contacts water, Didymo easily can be spread unintentionally by river users. Gear must be dried for a minimum of 48 hours or cleaned with a bleach solution to get rid of the algae.

The Ausable River Association in New York and the Mad River Association in Vermont have worked proactively to prevent the introduction of Didymo into their watersheds. River stewards monitor popular river recreation sites, discussing Didymo and the threat of aquatic invasive species transport on gear and equipment.

More on DIdymo

- Didymo Fact Sheet (USDA National Invasive Species Information Center)

- Didymo Fact Sheet (US EPA)

- Didymo Fact Sheet (New Hampshire DES)

- Didymo Fact Sheet (NYS Invasive Species Clearing House)

Eurasian Watermilfoil

Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum), first discovered in the Basin in 1962, is found in several areas in the Lake and Basin. In some areas infestations are severe; however, most are light or moderate. Detailed watermilfoil studies have been conducted for many of Lake Champlain’s bays and for 41 other lakes within the Basin, but many areas have had little or no study. Eurasian watermilfoil is not easily controlled because it is a perennial and spreads by plant fragments transported by waves, wind, currents, people, and animals.

Controlling Eurasian watermilfoil is costly. Millions of federal, state, and local funds (excluding salaries and administrative costs), and thousands of volunteer hours have been spent on controls in New York and Vermont lakes and ponds since 1982. Control mechanisms that have been employed in the Basin include mechanical harvesting, diver-operated suction harvesting, installation of benthic barriers, fragment barriers, handpulling, hydroraking and herbicides. Use of biological controls such as the release of a species of aquatic weevil are experimental at this time.

More on Eurasian Watermilfoil

- Infestation maps from Vermont Agency of Natural Resources

- Eurasian Watermilfoil Fact Sheet (VT DEC)

- Eurasion Watermilfoil Fact Sheet (Adirondack Park Invasive Plant Program)

Golden Clam

The Golden clam (Corbicula fluminea) is hermaphroditic bivalve that is native to tropical areas in Asia, the eastern Mediterranean, and Australia. Their shells are brown or yellow-green with thick concentric rings on the outside and smooth with a purple tinge on the inside. They are generally smaller than a penny in diameter but can reach sizes of up to 5cm. Unlike zebra mussels, which colonize on hard surfaces, the clams prefer open, sandy bottom areas with limited plant growth, where they can form dense, thick mats. Golden clams usually reproduce twice annually with one clam capable of releasing up to 2,000-4,000 offspring each cycle. The literature suggests that water temperatures must rise above 59 degrees Fahrenheit (15 degrees Celsius) for the clams’ reproductive cycle to become active.

Golden clam was discovered in Lake Champlain near Whitehall, New York in the fall of 2024. A volunteer with the Lake Champlain Committee made the discovery while conducting a survey at the South Bay boat launch, which is owned and operated by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Progress is underway to assess the significance of this introduction and determine next steps.

Golden clam was initially discovered in Lake George in August 2010 in the Village of Lake George. Scientists initially documented as many as 600 clams per square meter, covering an area of approximately 2.5 acres. The Lake George Golden Clam Rapid Response Task Force was quick to launch efforts to eradicate the clam.

Over the period of six years (2010‐2015) the Task Force researched state of the art management methods and attempted to eradicate any identified clam populations in the lake. These efforts consisted mostly of covering the affected lake bottom with ‘benthic barriers’, sandbags, and rebar to eliminate these populations by lowering the oxygen levels. This was a method long‐employed in Lake Tahoe following extensive research. The Lake George benthic barrier control efforts were highly effective (96‐100% mortality in most cases). However, if a site did not achieve a 100% mortality rate, the clams rebounded quickly. In sites where no clams were found the year after treatment, they were identified in small populations the next year.

After costly but ultimately unsuccessful management efforts, the Task Force halted barrier treatments in 2016. Research continues in clam biology, potential lake impacts, and potential future treatments.

Annual lake‐wide surveys provide a sense of how clam populations are spreading and the general population densities of known locations. In low densities, these invasive clams seem to have no impact on Lake George. In much higher densities (thousands of clams per square meter), there is long‐term concern about potential water quality impacts and impacts to beach areas from excessive dead clam shells.

More on Golden Clam Management

- For press releases, photographs, and reports please visit the Lake George Asian Clam Eradication Project website.

Japanese Knotweed

Japanese knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum) was first introduced to the United States as an ornamental plant in the late 1800s because of its appealing flowers. It was also used for erosion control because of its rapid and prolific growth. It has subsequently spread into the wild across most of the United States, including the Lake Champlain Basin. It spreads via underground rhizomes that easily fragment and spread to other areas. This is especially problematic along streambanks where natural forces contribute to the spread of knotweed.

Japanese knotweed has already altered thecharacter of the Lake Champlain Basin’s riparian zones. Knotweed grows early in the season and is very dense, excluding native plant species, decreasing diversity and altering wildlife habitat. It also quickly rebounds from disturbances such as flooding. In the fall, when the plant dies back, the dead stems and leaf litter form a dense mat that decomposes slowly, further inhibiting native plant growth. Dense growth in riparian zones also hampers recreational uses such as swimming, fishing and boat access. When dense stands are removed from riverbanks there is an increased risk of erosion until native plants reestablish themselves.

Japanese knotweed continues to spread throughout the Lake Champlain Basin. The spring flooding in Lake Champlain in 2011 and more frequent and intense storms such as tropical storm Irene and Lee in 2012 caused significant spread of this species along the lake shore and stream corridors.

While there are several methods to control knotweed, they are expensive and generally require intensive labor. Even though some people enjoy the taste of the young shoots and the appearance of the plant as an ornamental, it is an undesirable resident of the Basin.

More on Japanse Knotweed

- Japanese Knotweed Alliance Website

- Japanese Knotweed Control Options (University of Georgia / USDA)

- Japanese Knotweed in Vermont PDF Fact Sheet (Nature Conservancy)

Purple Loosestrife

Purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) is native to Eurasia and has been present in New England for almost 100 years. It now can be found throughout the temperate portions of the United States and Canada. It has no natural predators in North America.

Although it adds vibrant swaths of color to the Basin’s roadside ditches and wetlands, purple loosestrife is an unwanted alien to this region. It crowds out native wetland plants such as cattails, grasses, sedges, and rushes, and is of almost no value to wildlife. Loosestrife is quick to invade many habitats, including wet meadows, marshes, riverbanks, and the edges of ponds and reservoirs. Gardeners can unintentionally increase its spread by planting it in home gardens. Even sterile varieties, often sold by nurseries, are now considered a problem and should never be planted

The VT DEC, APIPP and other NY partners have been working for several years to determine whether an introduced beetle (Galerucella) that eats loosestrife can help control the plant’s spread. This beetle has been placed in several test wetlands throughout Vermont and New York and has shown promising results.

More on Purple Loosestrife

- Purple Loosestrife Fact Sheet (The Nature Conservancy and VT ANR)

- Purple Loosestrife Profile (USGS and NOAA Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System)

- Adirondack Park Invasive Plant Program

Rusty Crayfish

The rusty crayfish (Orconectes rusticus) is native to Ohio and Tennessee but has spread to many other parts of the country including New York and all New England states (except Rhode Island). They have been found in Lake Carmi and were spotted in the lower Winooski River in 2005. Rusty crayfish typically displace or hybridize with native crayfish populations and prey on native plants, benthic invertebrates, fish eggs, and small fish. Their aggressive predation of native species decreases diversity, destroys habitat, and has an overall negative impact on many aquatic ecosystems. Rusty crayfish may also spread Eurasian watermilfoil by fragmenting the plants and defoliating native flora which clears the way for further milfoil infestation.

There are currently no successful management techniques for rusty crayfish once a population is established.

More on Rusty Crayfish

- Rusty Crayfish Fact Sheet (University of Minnesota)

- Rusty Crayfish Distribution Map (USGS)

Sea Lamprey

The sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) is a nuisance species in the Lake Champlain Basin. First reported in Lake Champlain in the 1920s, sea lamprey were assumed to be non-native, invasive species that had entered through the Hudson/Champlain canal in the 1800s. Today, it is unclear whether sea lamprey are truly invasive. Recent genetic analysis suggests that sea lamprey may in fact be native to Lake Champlain. Regardless, conditions favoring sea lamprey growth have allowed their populations to reach excessive and problematic levels.

During a brief period in their 5- to 6-year life cycle, sea lamprey are parasites that have been associated with the decline of Lake Champlain trout and salmon populations. Sea lamprey spawn in tributaries to the Lake, where the non-parasitic larvae stay for about four years until they metamorphose into the parasitic form and migrate into Lake Champlain to feed on the blood and body fluids of host fish using their circular, suctioning mouths and small, sharp teeth. Their preferred host fish are salmon, lake trout, and other trout species, but sea lamprey wounds have been found on walleye, lake whitefish, northern pike, burbot, lake sturgeon, and many other fish in Lake Champlain. A Great Lakes study estimates a 40-60% mortality rate for fish wounded by sea lamprey.

Sea lamprey impacts come at both an ecological and economic cost. Several of the fish species commonly attacked by sea lamprey are declining, and fishing brings millions of tourism dollars into the Basin annually. The New York Department of Environmental Conservation estimates that sea lamprey damages have cost Lake Champlain Basin businesses at least $29 million.

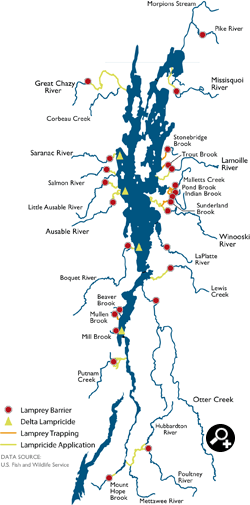

The Lake Champlain Sea Lamprey Control Program was initiated in 2001 and applies an integrated pest management approach, using barriers, traps, and lampricides to control sea lamprey populations. In 1990, experimental application of the lampricide trifluoromethyl-4-nitrophenol (TFM) to Lake Champlain tributaries began, followed by application of Bayer 73 to tributary deltas in 2001 to target ammocoete (larval) populations that live in the tributaries and deltas before migrating to the lake as parasites.

Lampricides are extremely effective population control tools, but can stress local non-target amphibians, fish, mussels, and other biota. To reduce negative effects of lampricides, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), VT Fish and Wildlife Department, and NY State Department of Environmental Conservation work together to carefully monitor the amount of lampricide used and use non-chemical approaches whenever possible.

In May 2014, a new sea lamprey barrier was opened on Morpion Stream, a tributary to the Pike River in Notre-Dame-de-Stanbridge, Québec. The installation of this barrier was accomplished with international cooperation between the town of Notre-Dame-de-Stanbridge and the USFWS, who share barrier operation and ownership. The barrier captures sea lamprey as they swim upstream in the spring to spawn in the Morpion Stream without affecting non-target species.

The benefits of these control efforts are seen in assessments of sea lamprey wounding rates in recent years. In 2010, sea lamprey wounding rates on Atlantic salmon had decreased from a high of 79 wounds per 100 fish to meet the target of 15 wounds per 100 fish. In 2011, wounding rates on both Atlantic salmon and lake trout were within 5 wounds per 100 fish of the targets for each species for the first time since monitoring began in 1985.

More on Sea Lamprey

- Lake Champlain Sea Lamprey Control (NYSDEC)

- Lake Champlain Sea Lamprey Control (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service)

- Impact of Sea Lamprey on Salmon and Trout (LCBP State of the Lake)

Spiny Waterflea

Native to Eurasia, the spiny water flea arrived in the Great Lakes in ballast water in the 1980s, and have spread to other water bodies since. They feed on tiny crustaceans and other zooplankton that are foods for fish and other native aquatic organisms, putting them in direct competition for this important food source. Spiny water fleas are small crustaceans, and cause no known risk to people or human health. The tail spines of the spiny water flea hook on fishing lines and foul fishing gear. Spiny water fleas have altered zooplankton communities in some lakes where they have spread. They have rapid reproductive rates and in warmer water temperatures these water fleas can hatch, grow to maturity, and lay eggs in as little as two weeks. The “resting” eggs of spiny water fleas overwinter in lake sediment and remain dormant for long periods of time. The eggs are resistant to drying which has implications for the types of actions that will prevent their spread.

The spiny water flea is the first aquatic invasive zooplankton to be confirmed in Lake Champlain. The Lake Champlain Long-term Biological Monitoring Program first confirmed the presence of the spiny water flea in the Lake in August 2014. It is unknown how spiny water flea spread to Lake Champlain. They can survive in as little as a thimble of water. Adults, juveniles or eggs may have entered Lake Champlain in water that was not drained from a boat, in a vessel compartment, or attached to equipment such as anchor lines or fishing equipment. They might also have drifted through connected waters from the Champlain Canal or the outlet of Lake George, where they were discovered in 2012.

The Lake Champlain Basin Aquatic Invasive Species Rapid Response Task Force has determined that eradication of spiny water flea in Lake Champlain is not technically feasible. Efforts will be focused on spread prevention measures, including promoting the “Clean, Drain and Dry” message and other education initiatives, continued sampling in water bodies in the Basin, and strategic siting of boat wash and decontamination stations.

More on Spiny Water Flea

- Spiny Water Flea Fact Sheet (USGS)

- Spiny Water Flea Fact Sheet (Minnesota DNR)

Tench

Tench (Tinca tinca) are native to Europe and similar to carp that live on lake or river bottoms. They are a slimy, slow moving carnivorous member of the minnow family that prefers tranquil, shallow water and weedy areas where they feed on invertebrates. In Europe, the tench is harvested and consumed by people.

The tench was first caught and identified by two fishermen on the Great Chazy in New York in May 2002. Brian Ellrott from UVM’s Rubenstein Science Lab and Drew Price from the Center for Lake Champlain caught the 20- inch specimen near the lamprey barrier dam on the Chazy River. It is unknown how the tench found its way to the Great Chazy, although the Richelieu River already has a viable tench population.They are now found throughout northern Lake Champlain.

It is too early to tell the effects of the tench on Lake Champlain’s native species. Female tench may lay up to 600,000 eggs annually. The tench has a tendency to cloud the water where it lives by stirring up the bottom sediments. These fine sediments can suffocate the eggs and newly hatched fish of native species such as pike, perch or crappie.

More on Tench

- Tench Fact Sheet (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife)

- Tench Fact Sheet (USGS)

Variable-leaved watermilfoil

Variable-leaved watermilfoil (Myriophyllum heterophyllum) is native to the southern portions of the United States. It can crowd out native aquatic plants and can impede boating, fishing, and swimming. It spreads by stem pieces, roots, and seeds, and “hitchhiking” on boats and recreational equipment.

VLM was confirmed in the southern end of Missisquoi Bay in Lake Champlain in September 2009 and subsequently in the southern end of Lake Champlain in summer 2011. It is also distributed through several lakes in the Adirondack Park. Like Eurasian watermilfoil, variable-leaved watermilfoil is an aggressive, rapidly-growing nonnative species.

More on Variable-Leaved Watermilfoil

- Variable-leaved Watermilfoil Fact Sheet (VT DEC)

- Variable-leaved Watermilfoil sign (LCBP | PDF)

Water Chestnut

European water chestnut (Trapa natans) is an annual plant that can form dense mats, limit boat traffic and recreational use, crowd out native plants, and create an oxygen depleted zone uninhabitable to fish and other organisms. Is of little food value to wildlife. The plant must be controlled each year before its seeds drop to the lake bottom where a small percentage can remain viable for up to twelve years.

First documented in Lake Champlain in the 1940s, water chestnut is a high priority species for management, and notable progress in controlling it has been made. Since the 1960s, its local range has fluctuated in correspondence with management funding levels. It was nearly eradicated by the early 1970s, but lack of consistent control allowed water chestnut to expand its range. Water chestnut is known to occur in two places in Lake Champlain in 2011, but it has also infested other inland water bodies in the Basin. The largest infestation is in the south lake of Lake Champlain. By 1997 it was found 52 miles north of Whitehall. A Pike River infestation has been eradicated as of 2007 and a Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge population is under careful management.

The South Lake population is aggressively managed by mechanical and hand harvesting methods. A management program begun in 1998 with an average annual budget of $500,000 has greatly reduced this population. Due to the program’s success, mechanical harvesting was needed only as far north as the Dresden Narrows, VT by then end of 2012. Remaining areas are managed by handpulling.

More on Water Chestnut

- Maps and additional information (Lake Champlain Basin Atlas)

- Water Chestnut Fact Sheet (Invasive Plant Atlas of the United States)

- Water Chestnut Fact Sheet (VT DEC)

White Perch

White Perch (Morone americana) are a relatively new nonnative invasive species of increasing concern in the Lake. In 2003, Québec researchers found that white perch far outnumbered native perch in Missisquoi Bay and are now the Bay’s most abundant fish. White perch are now found throughout Lake Champlain and in the lower sections of its tributaries. They may displace native perch by feeding on their larvae and compete for zooplankton which can lead to an increase in algal growth. White perch are also known to prey on walleye eggs along with white crappy, which has contributed to the significant decline in the walleye population.

More on White Perch

- White Perch Fact Sheet (Iowa Department of Natural Resources)

- White Perch Fact Sheet (USGS)

Zebra Mussels

The zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) is a small freshwater mollusk native to the Caspian and Black Sea regions of Eurasia. They are thought to have been transported to North America in the ballast tanks of ships. Since their arrival in the Great Lakes around 1986, zebra mussels have resulted in millions of dollars of damage and lost revenues.

Adult zebra mussels have spread throughout nearly all of Lake Champlain since they were first found in 1993. Fewer mussels are found in Missisquoi Bay where refuges of native mussel populations are holding on but are increasingly threatened. In 1999, adult zebra mussels were also found in Lake George, NY near Lake George Village and in Lake Bomoseen, VT. Zebra mussel veligers have been found in Lake Dunmore, Hortonia, and Carmi, but no adults have been found to date.

Zebra mussels can clog residential, municipal and industrial water intake pipes, foul boat hulls and engines, cover recreational beaches and lake bottoms cutting the feet of swimmers, and obscure underwater and archeological artifacts. Zebra mussels take over spawning habitats for Lake Trout, Smelt, and other fish. They consume microscopic plants and animals in large quantities, in competition with juvenile fish and native mussels. This also has the effect of increasing water clarity, which has some benefits, but can aid the spread of invasive plants to deeper areas of the lake. Zebra mussels have begun to kill many of Lake Champlain’s native mussels by attaching to their shells, preventing them from opening to feed and respire. Seven mussel species native only to the Basin are now severely threatened.

Because no effective zebra mussel control methods exist, efforts are focused on education to slow their spread to other lakes. Management actions have focused on controlling the mussels’ attachment to surfaces and water intake pipes and on preventing further spread. The impacts of zebra mussel infestations on the ecosystem and underwater cultural artifacts are also not well understood, but ongoing worldwide research may offer some understanding of possible effects.