Open Water

The open water in Lake Champlain provides a variety of habitat for microscopic plankton, aquatic plants, fish, and other wildlife. Over long periods of time, species in the lake have adapted to distinct conditions. Many organisms prefer relatively shallow water where light and dissolved oxygen are abundant, while others can survive in deeper and darker regions of the lake.

The different regions and zones of the lake are defined by temperature, light penetration and absorption, and water chemistry (among other factors and processes), which can all influence the density of water.

Lakes can sometimes be separated into distinct layers based on density. This separation into layers is called stratification and determines the kinds of habitat available for aquatic plants, plankton, fish, and other wildlife. Lakes can also be categorized by the availability of light.

Temperature Stratification

Temperature affects the density of water. Water becomes denser as it cools, reaching its maximum density at 4 degrees Celsius (39 degrees Fahrenheit). As water cools below 4 degrees, it becomes less dense. This is why ice floats. As water warms from 4 degrees, it also becomes less dense.

Temperature (or thermal) stratification refers to the layering of water based on temperature differences: warmer, less dense water will form a distinct layer above cooler, denser water.

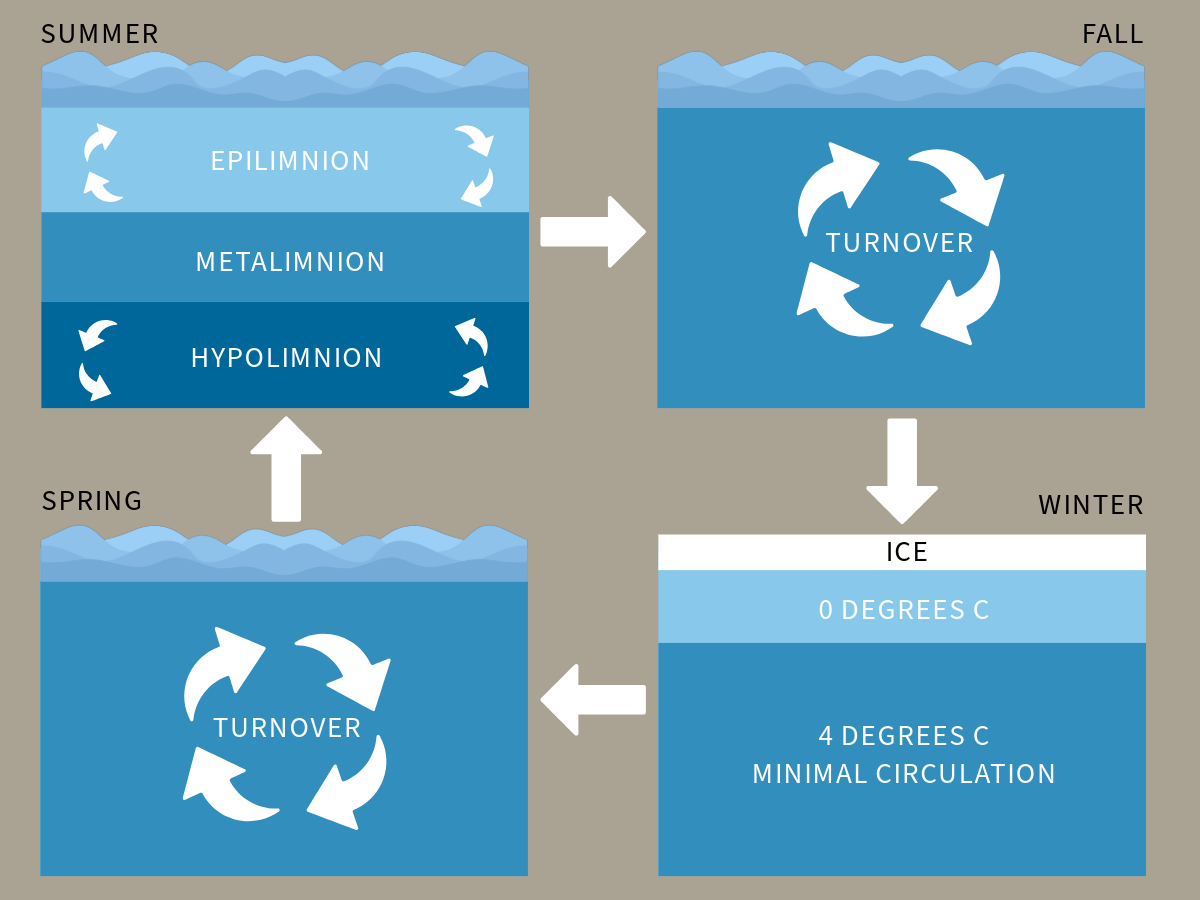

Where lakes or lake regions are deep enough, temperature stratification in lake can create three main thermal layers: the epilimnion, metalimnion, and hypolimnion.

The epilimnion is the uppermost layer, where sunlight warms the water, creating a zone of consistent temperature, relatively high dissolved oxygen levels, and active mixing due to wind. Beneath this lies the metalimnion, where temperature changes rapidly with depth; this steep gradient is called the thermocline. The hypolimnion is the deepest layer, characterized by cold, dense water, often with relatively low levels of dissolved oxygen.

For lakes or lake regions that are deep enough, these layers are most pronounced in the summer months. In the fall and spring, parts of Lake Champlain undergo a mixing called “lake turnover.” As the air temperature drops throughout the fall, the lake cools and mixes. During turnover, oxygenated surface waters cool and sink, supplying oxygen to the bottom of the lake, and water from the deeper hypolimnion layer rises to the surface. In the spring, water warms, any ice on the surface of the lake melts, and wind-driven mixing can mix the lake once again.

Seasonal mixing is an important process that replenishes oxygen and distributes nutrients throughout the lake. In the hypolimnion, bacteria feed on organic matter that has settled on the lake bottom. This important decomposition process consumes oxygen. When dissolved oxygen levels are too low, few organisms can survive. Nutrients and oxygen must also be circulated in order for plankton, aquatic plants, and fish to survive. Phytoplankton and algae form the base of the food web and are prey to zooplankton and small fish. Larger fish may also feed on plankton or smaller fish. Nutrients and oxygen must be well-distributed throughout the water column for species at all levels of the food web to survive.

Photic Zones

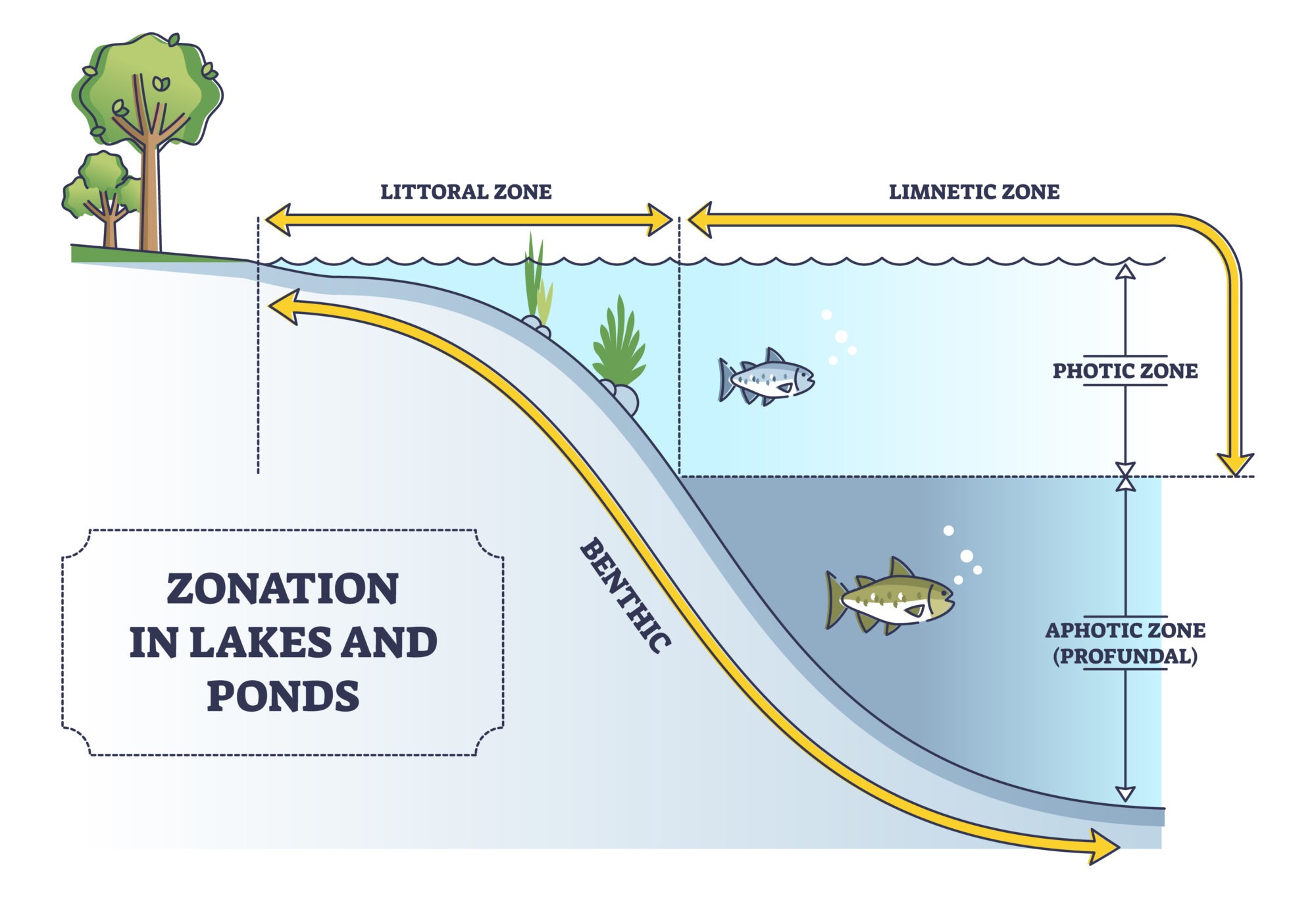

Lakes can also be divided into ecological zones based on the amount of light that is available for photosynthesis. Each zone is home to aquatic life adapted to specific temperature and light conditions.

The littoral zone is the shallow area near the shore, where sunlight reaches the bottom and supports rooted plants and diverse aquatic life. Vegetation, rocks, and wood create physical structure that supports a wide variety of aquatic and terrestrial life.

Moving outward from the littoral zone lies the limnetic (or pelagic) zone, the open water area where sunlight penetrates but doesn’t reach the bottom, supporting plankton and fish populations.

Together, the littoral and limnetic zones make up the photic zone of the lake.

In deeper waters where light is insufficient for photosynthesis lies the aphotic (or profundal) zone. This water sometimes contains less dissolved oxygen than the well-mixed upper layers and generally supports less aquatic life.

The area along the lake bottom is known as the benthic zone and may be shallow or deep. This zone is home to decomposers and, in deeper areas, organisms adapted to low light and oxygen levels. Lake Champlain is home to several species of benthic fish, including catfish and sturgeon, which reside in the benthic zone and feed on small, bottom-dwelling creatures.

References: Encyclopedia of Inland Waters, W.M. Lewis; Lake Champlain Committee; Michigan Sea Grant; National Ocean Service – NOAA; Alabama Wildlife Federation